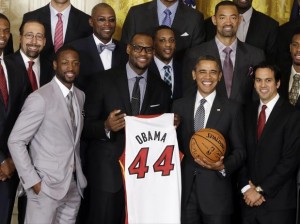

Three years ago after “The Decision” and the free agent signing of Chris Bosh, the Miami Heat were declared the NBA Champions for the next 10 years. Who could beat them? They were loaded. They had filled the requirements of “The Championship Formula” and the future was set. Barring a catastrophic injury (or a cataclysmic Game 7 against the Pacers), the trophy was ready to be engraved!

Three years ago after “The Decision” and the free agent signing of Chris Bosh, the Miami Heat were declared the NBA Champions for the next 10 years. Who could beat them? They were loaded. They had filled the requirements of “The Championship Formula” and the future was set. Barring a catastrophic injury (or a cataclysmic Game 7 against the Pacers), the trophy was ready to be engraved!

What is this formula that wins championships? Is it something new? Does it really work or is it something that reporters make up to have something to talk about? Can it be created on demand?

All of these questions occupy the minds of NBA owners, GMs and coaches, creating many sleepless nights and many more gray hairs. Why do you think that coaches seem to age faster than the President does?

Let’s start at the beginning. “The Championship Formula” of today starts with a Big 3. Then it adds role players and specialists since the salary cap precludes a Big 4 or Big 5. In the days when I played, the Formula was different. Teams had as many as 7 current and former all-stars on their roster. Usually two came off the bench and reveled in being in the role of “difference maker” (think Michael Cooper, Vinnie Johnson, Bill Walton, and Mychal Thompson). The GTOAT (Greatest Team of All Time, Bill Russell’s Celtics) had 7 future Hall of Fame players on their roster at the same time!

Step One, what does it take to win a championship? The simple answer is that you need to beat the same team 4 times. Then you need to do that to 4 different teams. What separates the teams that make the playoffs from the teams that win the playoffs? Most people think that the team with the better talent wins. That is a myth. The accumulation of top talent is merely the cost of entry. The ability to win close games is the single most valuable factor in winning championships. That only comes with experience and heartache.

Step One, what does it take to win a championship? The simple answer is that you need to beat the same team 4 times. Then you need to do that to 4 different teams. What separates the teams that make the playoffs from the teams that win the playoffs? Most people think that the team with the better talent wins. That is a myth. The accumulation of top talent is merely the cost of entry. The ability to win close games is the single most valuable factor in winning championships. That only comes with experience and heartache.

When you play the same team over and over, a playoff series becomes a constant stream of adjustments. Winning teams set up a strategy that accounts for a dizzying array of countermoves. They have the flexibility to show different looks and counteract the other teams moves. They keep something in reserve for special occasions.

Remember the role player specialists that I talked about earlier? Here are the roles that they need to fill.

Each team needs 3 star players to have sufficient horsepower win at the championship level. Two of them need to be able to score at any time if left with a single defender. The ENTIRE REST OF THE PLAYING ROSTER needs to be good enough to keep the defense honest and occupied to let the stars make a play. Otherwise teams will double- and triple-team your stars, forcing the big plays to be made by guys unable to come through.

The Thunder were on the brink of dominance. James Harden gets moved and Russell Westbrook blows a knee and POOF, Kevin Durant isn’t enough to get them there by himself. He gets hounded and overworked with no one to provide the needed balance. The 3 star role went unfilled and they went down. Ditto Dallas and Dirk.

The remaining favorites have the 3 star role filled with Tim Duncan, Manu Ginobili and Tony Parker for the Spurs and LeBron James, Chris Bosh and Dwyane Wade for the Heat. The upstart Pacers have the same with Roy Hibbert, David West and Paul George.

The remaining necessary roles:

Shooter: Winners need a lights out 3-point shooter who can’t be left alone. They stretch defenses to the point where big holes are left open. They are so valuable that they don’t need to be able to do anything else. The Bulls had Steve Kerr, The Lakers had Michael Cooper, the Heat have Ray Allen and a bench full of shooters. Each team views this guy as a must-have.

Shooter: Winners need a lights out 3-point shooter who can’t be left alone. They stretch defenses to the point where big holes are left open. They are so valuable that they don’t need to be able to do anything else. The Bulls had Steve Kerr, The Lakers had Michael Cooper, the Heat have Ray Allen and a bench full of shooters. Each team views this guy as a must-have.

The Expendables: This is the enforcer big who is sent out to use his fouls well. This way the stars don’t get worn down defending or get in foul trouble themselves. They bang drivers, clog the middle, and get in scuffles. On offense, all they do is be available for a dump off bucket or offensive rebound. They only score if left open and NEVER have a play called for them. They just have to be alert enough to occupy a defender. They are never in at the end when a three is needed since they will be left unguarded. Chris “Birdman” Anderson is the perfect example this year.

(Until we saw what Roy Hibbert has been doing against the Heat, the belief that the dominant scoring center of old went the way of the dodo bird into extinction. But that’s another story!)

The current playoff picture displays the effectiveness of the balanced team. The Heat have “The Unstoppable Force” in James. They have the “Keep you honest” stars in Wade and Bosh. They are surrounded with shooters to spare to keep defenses from collapsing on them. And they have Birdman doing his best Tasmanian Devil impression.

Plus THEY WIN CLOSE GAMES. Indiana let Game 1 slip away before winning Game 2. Imagine going home with a 2-0 lead? Now they have to beat Miami 5 times. When you give back a game that you had won, you still need 4 more wins. Miami wins games when they shoot well from outside. In their loses, poor shooting has led to LeBron being doubled by Indiana’s big men. Consistent outside shooting forces the Pacers to “pick their poison”. Give up threes or let LeBron go one on one.

I guess this becomes more relevant with the news that Hollins is allegedly ready to leave because of his conflicts with management’s love of analytics in shaping the team, and particularly with Hollinger’s alleged interference. You have an interesting perspective in your article in that you present a “qualitative” analytic view of what a playoff-tough team requires. What, in your mind might be the main advantages and disadvantages between this and one that relies on quantitative analytics, assuming both are state of the art?

Would be interested to hear your thoughts on the Memphis Grizzlies. They did extremely well during the regular season and the first two rounds of the playoffs with only one capable isolation player (Conley) among their big three (Gasol, Randolph, and Conley) and zero lights-out three point shooters. They traded away their best isolation scorer (Gay) and let their second-best isolation scorer walk (Mayo). Adimittedly, both were not playing up to par during their last stint with the Grizzlies, and the offense actually became more efficient during the regular season after Gay left. The Gay trade was seen as a victory for quantitative analytics vs. “gut” evaluation of talent, but was that the case? Could they have done better against the Spurs with Gay and/or Mayo? Or would it have been a further hinderance to their style of offense? Thanks.