When the NBA has had father-son stories, the dad always watched from the stands like Joe Bryant, Rick Barry and Stan Love; or from the other bench like George Karl and Mike Dunleavy Sr.

When the NBA has had father-son stories, the dad always watched from the stands like Joe Bryant, Rick Barry and Stan Love; or from the other bench like George Karl and Mike Dunleavy Sr.

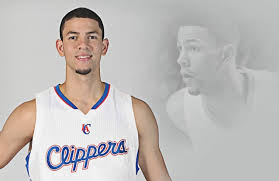

Now comes Doc Rivers, who’s not only watching 22-year-old Austin, but putting him in and subbing him out as the first man in the NBA to coach his son.

It’s at least a little awkward, if only in a domestic comedy sense.

Having acquired his child in his role as Clipper president, Doc may one day have to cut him, which will definitely tick off Austin’s mother.

“The first thing I did was call my mom,” Austin said of negotiations that led to last week’s trade. “She’s the one that got to deal with this and she was a wreck the first night. She was calling me: ‘Like what if this happens?’”

Unfortunately for Austin’s mom and Doc’s wife, Kristen, the family affair got off to a slow start.

Brought in to replace backup point guard Jordan Farmar, who wasn’t able to replace Darren Collison, Austin played 12 nervous minutes in his Clipper debut, failing to score and going 0-4 from the floor in the 126-121 loss to the Cavaliers.

Brought in to replace backup point guard Jordan Farmar, who wasn’t able to replace Darren Collison, Austin played 12 nervous minutes in his Clipper debut, failing to score and going 0-4 from the floor in the 126-121 loss to the Cavaliers.

The Clippers led by seven when Austin came in alongside Chris Paul with 2:23 left in the third quarter.

When Paul sat down to start the fourth, the lead was down to three.

When LeBron James hit a 10-footer to put Cleveland up by three 2:53 later, CP3 jumped up to check back in… showing that basketball, not blood, still determines their pecking order.

The problem isn’t the conflict of interest, because Doc and Austin look professional enough to deal with it.

The problem is that the bench, one of the greatest strengths when Doc arrived in 2013, has become one of the biggest weaknesses, even with perennial Sixth Man of the Year candidate Jamal Crawford.

Asked recently how his team blew a 13-point third-quarter lead in a home loss to Atlanta, Doc said, “I had to sub at some point.”

Baby, baby, where did our bench go?

Doc has been a vast upgrade over the entirety of Clipper history, turning DeAndre Jordan into a Defensive Player of the Year candidate, Blake Griffin into an all-around player and Chris Paul into a fast-breaking point guard rather than one pounding the ball in the half-court.

More to the point, Doc pried owner Donald T. Sterling’s fingers off the basketball operation as a condition of taking the job, then when the owner self-immolated last spring, led the players in dissociating themselves from the man who signed their lavish paychecks.

(Trying to mend fences a few days into the crisis, Sterling phoned Rivers, who declined to talk to him.)

In the process, Doc took the team into the second round of the playoffs, where a controversial foul call on CP3, breathing in the vicinity of Russell Westbrook as he heaved up a desperate three-pointer at the end of regulation, kept them from coming home up, 3-2, on the Thunder.

In the process, Doc took the team into the second round of the playoffs, where a controversial foul call on CP3, breathing in the vicinity of Russell Westbrook as he heaved up a desperate three-pointer at the end of regulation, kept them from coming home up, 3-2, on the Thunder.

Rivers was the Irreplacable Clipper, the one the league needed to make sure its racial scandal was limited to one kooky owner, rather than mushrooming into an issue between all NBA players and owners.

Everything the NBA did was in conjunction with Doc, sending in former Time Warner CEO Richard Parsons to confirm Rivers’ authority. Doc, not the league, signaled that merely selling the team to Sterling’s wife, Shelly, wouldn’t fly, limiting her to a ceremonial role.

Even with Steve Ballmer paying $2 billion, there was no question of replacing Doc. He got a five-year $50 million contract, becoming the game’s highest paid coach.

As an administrator, however, Doc was a rookie and an unlucky one, at that.

Moves for veterans like Jared Dudley and Spencer Hawes that looked good at the time didn’t turn out that way.

More debatable moves, trading Eric Bledsoe for J.J. Redick when Arron Afflalo, a better defender, was available for less, did turn out that way.

Matt Barnes, a key reserve on the NBA’s highest scoring bench alongside Bledsoe, became a starter when Dudley misplaced his jumper (which has since resurfaced in Milwaukee).

After one stellar season, Collison left when they gave their veteran’s exception to Hawes, needing a bigger backup for Jordan than Glen Davis.

Jordan Farmar, who was supposed to be good enough, wasn’t close, and too headstrong for Doc.

If Austin is a 1-2 or really a 2-1—a scorer more than a playmaker—Doc didn’t wait to see how it went, cutting Farmar the day he acquired his son.

If Austin is a 1-2 or really a 2-1—a scorer more than a playmaker—Doc didn’t wait to see how it went, cutting Farmar the day he acquired his son.

Not that trading for Austin is a problem, personnel-wise. Chris Douglas-Roberts, one of the two players they gave up, is a journeyman; Reggie Bullock, the other, was averaging 2.6 points.

Of course, if trading for Austin becomes a coup, that will be a surprise, too.

Austin arrived knowing his role–”Chris and Blake are the leaders and everybody else behind them are really guys who are role players”–but has to show he can fulfill it.

No one knows his potential better than father, but the thought of coaching Austin gave Doc pause.

“We had a small opportunity this summer,” said Rivers, “and for me, I was like, ‘Ah, I don’t know.’… The fit probably swayed me more than the father part swayed me, I can tell you that.”

Unfortunately, backup point guard may not be their biggest issue.

Doc had to deny that his players don’t get along after NBA.com’s respected David Aldridge wrote, “Here’s the unvarnished opinion of someone who knows that team well: ‘They don’t like each other.’”

“It doesn’t matter,” responded Doc, in a less than adamant denial, “but I don’t get that sense, no.”

Actually, it matters a lot in the arch-competitive West. If the Spurs are one-for-all, all-for-one, as are the Warriors, Grizzlies, Trail Blazers, Mavericks, et al., it’s not good to be the elite contender with inter-personal issues.

Fathers have coached sons before. Cal Ripken Sr. managed Cal Jr. and Billy with the Orioles in 1987 and six games of 1988… making it awkward when Dad was fired.

Not that Doc figures to go anywhere soon. And, if nothing else, he and Austin figure to get along.

Hall of Fame writer Mark Heisler is a founding member and regular contributor to SheridanHoops, the Los Angeles Daily News and Forbes.com. Follow him on Twitter.