In the late 1970s I was a very impressionable teenager desperately trying to be cool.

In the late 1970s I was a very impressionable teenager desperately trying to be cool.

But I didn’t want the charm of James Bond or the street smarts of The Fonz or the dance moves of Tony Manero. Besides, they were all fictional characters from movies and TV shows. I wanted my cool to be real.

I wanted to be Darryl Dawkins.

I wanted to be Darryl Dawkins.

Dawkins died Thursday, leaving us way too soon at the age of 58. He claimed to be from the planet Lovetron, which made sense because no one walking the hardwood of our planet could be that cool.

He was big and black and boisterous. He was a teenager making hundreds of thousands of dollars to tour the country and play basketball in front of huge crowds for the Philadelphia 76ers, the greatest traveling roadshow the NBA has ever seen.

I grew up in Brooklyn, and my father used to get Knicks tickets from business buddies who had season packages. Good seats, too – either behind the bench or the backboard, no more than eight or 10 rows back. I would go to about eight games every season. Always among them were the three times the Sixers came to The World’s Most Famous Arena.

When the Knicks were playing anyone else, we would take the F train from Carroll Street to 34th Street, grab something to eat on the crosstown walk and get to our seats about 10 minutes before tip. But when the Sixers were in town, we made sure we got there at least 30 minutes early, because the Sixers’ pregame layup line was so entertaining it should have had a separate price of admission.

Those Sixers squads had Joe “Jellybean” Bryant, Kobe’s dad; George McGinnis, a barrel-chested forward who was equal parts force and finesse; 7-footer Caldwell Jones; guard Lloyd Free, whose vertical was so impressive one of his nicknames was “The Prince of Mid-Air”; and, of course, Julius Erving, who didn’t invent dunking – he only perfected it.

Those Sixers squads had Joe “Jellybean” Bryant, Kobe’s dad; George McGinnis, a barrel-chested forward who was equal parts force and finesse; 7-footer Caldwell Jones; guard Lloyd Free, whose vertical was so impressive one of his nicknames was “The Prince of Mid-Air”; and, of course, Julius Erving, who didn’t invent dunking – he only perfected it.

One of them would dunk, and the rest of the pregame warmup would become an impromptu Slam Dunk Contest, drawing oohs and aahs from the crowd that rendered the home team completely irrelevant.

The Sixers also had Dawkins, who had a flair and style and personality that was bigger than his 6-11, 260-pound frame. His dunks had so much originality that he gave them names. My personal favorites were the “In Your Face Disgrace” and the “No-Playin’, Get-Out-Of-The-Wayin’, Backboard-Swayin’, Game-Delayin’.”

And when we squeezed through the suits and their sweethearts to get to the edge of the court and be as close as possible to this spectacle, it was Dawkins who we were there to see, hoping some of that interplanetary coolness would possibly rub off on us. We would shout to him, not giving one crap about who we were disturbing or offending.

“Darryl! My man! You are the coolest!”

“Darryl! My man! You are the coolest!”

“Give us one, Darryl! Two hands! Hang on the rim!”

“You are beautiful, brother!”

That last one, hurled from a pack of starstruck goofy white teenagers, got a smile out of him. We had an interaction with the unquestioned king of cool. Did you see that? Darryl Dawkins smiled at us.

Are you trying to tell me that wearing a tuxedo and sipping a martini at a baccarat table was cooler than this? Sitting on a motorcycle sporting a leather jacket with the collar popped? Wearing a white suit with a black shirt while hustling with a high-heeled honey amid fog and flashing lights? C’mon, gimme a break.

So what if Dawkins never really lived up to the hype after entering the NBA straight from high school? He entered the NBA straight from high school. My older friends were taking the police exam or trying to get a job as a longshoreman on the Brooklyn piers.

The Fonz? He dropped out of high school and became a grease monkey. After Dawkins took off his cap and gown, the next thing he put on was a Sixers uniform.

At that time, virtually every player in the NBA had gone to a college that was mentioned during his pregame introduction. But when Sixers PA announcer Dave Zinkoff – a character in his own right – introduced Dawkins at the Spectrum, he said, “From Maynard Evans High School in Orlando, Florida, number 53, Darryl Dawkins.” How cool was that?

Years later, on a short-lived TV show called “Sports Pros and Cons,” host Bob Trumpy asked Dawkins about jumping from high school to the NBA, couching the question by saying, “You were just 18 years old. There were a lot of dark alleys you could have walked into.”

To which Dawkins replied, “Look at me. I’m 6-11 and black. Who’s gonna bother me in a dark alley?”

Of course, Dawkins could fight. In Game 2 of the 1977 Finals, he threw a roundhouse at Portland’s Bob Gross after a tussle for a rebound. Gross ducked but Sixers teammate Doug Collins didn’t and took four stitches for trying to keep the peace. Portland’s Maurice Lucas sucker-punched Dawkins from behind in the neck and the two squared off before being separated. Both were ejected, and Dawkins took out his anger on the locker room, as colleague Jon Marks notes in his column, as he was covering that game.

When some guys get really angry, they put their fist through a window or a door. Or they smash a table. When the game ended and his teammates returned to the locker room, they found that Dawkins had broken a toilet.

When some guys get really angry, they put their fist through a window or a door. Or they smash a table. When the game ended and his teammates returned to the locker room, they found that Dawkins had broken a toilet.

Not a mirror. Not a paper towel dispenser. A toilet.

The next day, my mother was on the B41 bus headed to Brooklyn College, where she had gone back to school. A guy got on, paid his fare, walked down the aisle and started extending his palm to anyone who would slap it and saying each time, “Darryl Dawkins … Darryl Dawkins … Darryl Dawkins.”

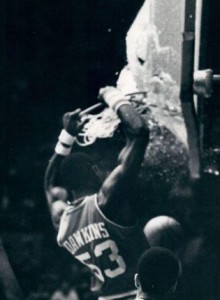

Backboards had no chance against a man strong enough to break a toilet. In 1979, Dawkins broke two in three weeks, smashing them to smithereens in mirror images of each other. The first one brought a shower of broken glass to the floor while the rim remained dangling. The second left the spider-webbed glass intact while the rim was yanked to the floor.

That prompted a visit to the commissioner’s office in New York, where Larry O’Brien politely asked Dawkins to please stop breaking backboards while announcing that further destruction by any player would result in a fine and suspension. In the offseason, the NBA decided to start using collapsible rims.

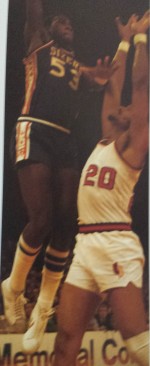

But that had little effect on Dawkins’ inimitable sense of style. During the 1977 Finals, he actually wore sneakers from two different companies. If you look closely at the picture below and to the right from Roland Lazenby’s book, “The NBA Finals: The Official Illustrated History,” you can see that Dawkins is wearing a Pony on his right foot and a Converse All-Star on his left. Do you really think James Bond could pull that off?

Dawkins also wore gold chains. During games. He wore more gold chains than Tony Manero, so many of  them that they would jangle when he jumped for dunks and rebounds. That brought about another permanent rule change from the league: You could not wear jewelry during games, because we could not have 300 guys trying to be as cool as Dawkins.

them that they would jangle when he jumped for dunks and rebounds. That brought about another permanent rule change from the league: You could not wear jewelry during games, because we could not have 300 guys trying to be as cool as Dawkins.

As entertaining as Dawkins and those Sixers teams were, they repeatedly came up short in their quest for a title. They were on the losing side in three NBA Finals before the summer of 1982, when they signed Moses Malone as a free agent. With the league MVP on board, the Sixers had to clear out the center position, sending Jones to Houston as compensation for Malone and trading Dawkins to New Jersey for a first-round pick. The Sixers finally won that elusive title that season, but I felt bad for Jones and Dawkins, who had to be sacrificed for the cause after battling the best they could against the likes of true greats such as Bill Walton, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Wes Unseld and Robert Parish.

Dawkins got some revenge the following season as the starting center for the Nets, who upset the defending champion Sixers in a best-of-five first round by winning all three games in Philadelphia. I was almost happy for him.

But my favorite Darryl Dawkins story came years later at All-Star Weekend in 2002. It was in Philadelphia, and Dawkins was named one of the judges for the Slam Dunk Contest. I thought it would be a good idea to ask the participants what they knew about Dawkins.

Steve Francis, Desmond Mason and Jason Richardson all had some knowledge of the coolest man to ever walk the face of the earth. But Gerald Wallace, a second-year player still not 20 years old, honestly claimed he didn’t know who Dawkins was. I tracked down “Chocolate Thunder” and informed him that Wallace had never heard of him.

“That’s OK,” Dawkins said, slyly smiling. “I never heard of him, either.”

Chris Bernucca is the managing editor and a featured columnist for SheridanHoops.com. Follow him on Twitter.