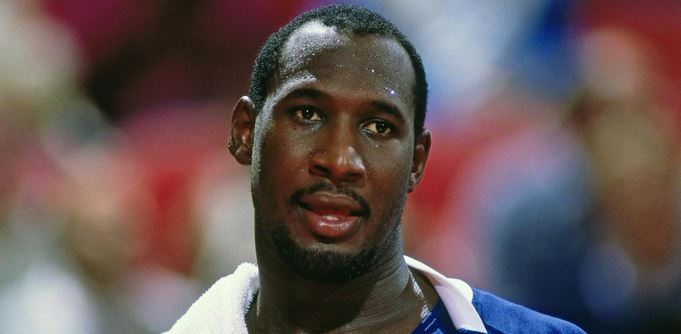

PHILADELPHIA– Like Peter Pan, Darryl Dawkins never wanted to grow up. And by definition, when you’re 6-11 and listed 251 lbs.—but probably bigger–and strong as an ox, that’s not easy.

PHILADELPHIA– Like Peter Pan, Darryl Dawkins never wanted to grow up. And by definition, when you’re 6-11 and listed 251 lbs.—but probably bigger–and strong as an ox, that’s not easy.

Everyone always wanted him to stop acting like a kid; to take the game, take himself, more seriously. They could see the raw talent was there—and every once in a while he’d put it on display, but only once in a while.

For the most part the big guy from Maynard Evans High in Orlando whom the Sixers tabbed with the fifth pick in the 1975 draft—the earliest a high school player had ever been taken—was more intent on having fun than playing serious hoops.

For the most part the big guy from Maynard Evans High in Orlando whom the Sixers tabbed with the fifth pick in the 1975 draft—the earliest a high school player had ever been taken—was more intent on having fun than playing serious hoops.

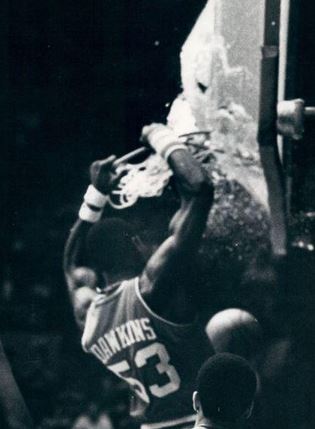

That’s the legacy Darryl Dawkins, a.k.a Chocolate Thunder, Double D, Sir Slam, The Dunkateer, Dawk and probably a few more, leaves behind following his stunning passing yesterday at 58. As prodigious as his dunks were—particularly the two that shattered the backboard … as powerful as he could be swatting away opposing shots or pulling down a rebound … as graceful as he could be swishing a jumper from the wing … you were always left wanting more.

The problem was the man from Planet Lovetron with a suburb known as Chocolate Paradise didn’t have the same motivation.

Perhaps it’s unfair being so critical of a player who did, after all, average 12.0 points, 6.1 rebounds and 1.4 blocks, while shooting at a 57.2 percent clip over 12 full seasons and snippets of two others. It was just when you saw Dawkins’ potential—like when he scored 27 points, grabbed nine rebounds and blocked eight shots in a 1982 playoff win over Atlanta–you wondered why such performances were the vast exception rather than the rule.

Sure enough, the rest of that postseason in which the Sixers—led by Julius Erving, Maurice Cheeks and Bobby Jones—went all the way to the NBA Finals, Dawkins never approached those numbers. Maybe that’s why after seven fun but frustrating seasons, the Sixers traded him up the turnpike to the New Jersey Nets for a No. 1 pick.

Sure enough, the rest of that postseason in which the Sixers—led by Julius Erving, Maurice Cheeks and Bobby Jones—went all the way to the NBA Finals, Dawkins never approached those numbers. Maybe that’s why after seven fun but frustrating seasons, the Sixers traded him up the turnpike to the New Jersey Nets for a No. 1 pick.

Coincidence or not, the following season Philadelphia finally won it all.

That was Darryl Dawkins the player, a big kid who was expected to be a world beater from the day he arrived but was ill-prepared for the challenge. Maybe it was to be expected. After all, the NBA had never taken a player straight from high school before—and this was no Kobe Bryant, Kevin Garnett or LeBron James, who’d been under the spotlight since puberty.

In contrast, when Darryl arrived in town he had no idea what to expect. This man-child in size was still a little boy at heart. In high school he manhandled the opposition, simply because he was so much bigger than everybody else.

In the NBA, of course, Double D quickly found out it would be a different story. No one was intimidated by his size. To succeed he’d have to work hard and refine his skills.

He did that to some extent, particularly offensively where he developed his jumper and some low post moves. But the rest of his game, the areas where you need to use your brains as much as your brawn, never came around as much as they could’ve, should’ve, would’ve had he been more truly committed.

Being in the big city, though, Darryl Dawkins wanted to enjoy life and have fun. He became a regular on the social circuit, buying a piece of a Center City nightclub which immediately became the hot spot in town. He’d hang with flamboyant players like Lloyd (who later became World B.) Free and Joe Bryant, whose son you may have heard of.

And then he’d step on the court, throw down a couple of monstrous dunks, and let everyone celebrate. Among those dunks were the one over Bill Robinzine which broke the backboard in Kansas City, which he infamous named the “If You Ain’t Groovin’ Best Get Movin’ — Chocolate Thunder Flyin’ — Robinzine Cryin’ — Teeth Shakin’ — Glass Breakin’ — Rump Roastin’ — Bun Toastin’ — Glass Still Flyin’ — Wham Bam I Am Jam!”

And then he’d step on the court, throw down a couple of monstrous dunks, and let everyone celebrate. Among those dunks were the one over Bill Robinzine which broke the backboard in Kansas City, which he infamous named the “If You Ain’t Groovin’ Best Get Movin’ — Chocolate Thunder Flyin’ — Robinzine Cryin’ — Teeth Shakin’ — Glass Breakin’ — Rump Roastin’ — Bun Toastin’ — Glass Still Flyin’ — Wham Bam I Am Jam!”

A month or so later he did it again, this time at home, which ultimately led the NBA to start installing breakaway rims before Shaquille O’Neal and others came along. While those of us in the Spectrum press box who witnessed it that night weren’t thrilled having to wait nearly an hour for them to get another hoop so the game could be resumed, it was still quite a moment.

So was Game 2 of the 1977 NBA Finals vs. Portland, when the precocious Dawkins squared off at center court with renowned enforcer Maurice Lucas. Both were ejected and the Sixers went on to win the game, taking a 2-0 series lead.

Coincidence or not, Philadelphia would not win another game in the series, as Bill Walton, Lucas and Trail Blazers were a different team from that point on.

But the real casualty of the night turned out to be the Sixers’ locker room facility. An enraged Dawkins took out his frustrations on the toilet; one of the rare times he let his emotions pour out.

Yet you couldn’t help but like Darryl. While athletes today are often surly and rude, this happy-go-lucky kid made even novice reporters feel at ease. And years later, when he was long retired and back in town making an appearance on behalf of the team, he hadn’t changed. Still warm, still fun-loving, still just a big kid at heart.

The ironic thing was in his later years, Darryl Dawkins tried to do the one thing he resisted most as a player: coaching. Now in his 50s Dawkins went to the deep minors, coaching briefly in Newark and Winnipeg, before finding a home in Allentown, Pa. There he coached the Pennsylvania Valley Dawgs of the U.S.B.L. until the franchise folded, before taking a position at the one place he’d never been: college.

The ironic thing was in his later years, Darryl Dawkins tried to do the one thing he resisted most as a player: coaching. Now in his 50s Dawkins went to the deep minors, coaching briefly in Newark and Winnipeg, before finding a home in Allentown, Pa. There he coached the Pennsylvania Valley Dawgs of the U.S.B.L. until the franchise folded, before taking a position at the one place he’d never been: college.

Lehigh Carbon Community College in remote Schnecksville, Pa., became his new home, where Dawkins tried to make a new life. Darryl hoped eventually someone might take a chance on him and bring him back to the NBA. Far too late in life he had come to the realization that if you want something bad enough, you have to work for it.

Sadly, now the two big men are gone from that Sixers non-championship era before Moses Malone joined Doc & Co. in 1983 and paid off their “We Owe You One!” debt. Caldwell Jones, the gentle giant who tried unsuccessfully to tutor Dawkins, died less than a year ago.

And Dawkins’ death lies shrouded in mystery. While his family says he succumbed to a heart attack at Lehigh Valley Hospital in Allentown, an autopsy will be performed today.

But as an outpouring of affection poured in from former teammates, former opponents, coaches, even NBA Commissioner Adam Silver who would see Darryl regularly at All-Star Weekend when he’d often be among judges at the dunk contest, it’s obvious this one hurts the hoops community. Maybe it’s because watching Darryl Dawkins brought out the little kid in all of us, the guy who wouldn’t listen to grownups because he was simply having too much fun.

No, he never grew up. And now Chocolate Thunder is off to play in Never Never Land.

ELATED: TWEET OF THE NIGHT: REACTION FROM AROUND THE NBA TO DARRYL DAWKINS’ DEATH)

Jon Marks has covered the Philadelphia 76ers from the days of Dr. J and his teammate, Joe Bryant (best known as Kobe’s dad). He has won awards from the Pro Basketball Writers Association and North Jersey Press Club. His other claim to fame is driving Rick Mahorn to a playoff game after missing the team bus. Follow him on Twitter.